November 9, 2015

After the October 20th strike on the Sarmin Hospital in Idlib, Dr. Tennari described the reality facing healthcare workers in hospitals in Syria: “When I am in the hospital, I feel like I am sitting on a bomb,” he said. “It is only a matter of time until it explodes. It is wrong – a hospital should not be the most dangerous place. I wish I could say that targeting a hospital in Syria is unique, but is not.”

After the October 20th strike on the Sarmin Hospital in Idlib, Dr. Tennari described the reality facing healthcare workers in hospitals in Syria: “When I am in the hospital, I feel like I am sitting on a bomb,” he said. “It is only a matter of time until it explodes. It is wrong – a hospital should not be the most dangerous place. I wish I could say that targeting a hospital in Syria is unique, but is not.”

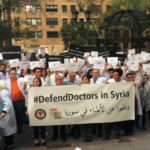

On October 29, 2015, over 200 people gathered in Dag Hammarskjold Plaza in New York City to call for an end to attacks on healthcare facilities like the one in Idlib.

The Syrian American Medical Society, Physicians for Human Rights, and Doctors Without Borders held a “die-in” to draw attention to the more than 679 healthcare professionals who have been killed since the start of the Syrian conflict in March 2011. Medical professionals, students, volunteers, and supporters from the community assembled in white coats holding signs representing each one of the hundreds of healthcare workers who have been shot, bombed, executed, or tortured in Syria. The Syrian government is responsible for 90% of the deaths of medical workers. Attendees lay still on the ground with their eyes closed to serve as a powerful visual reminder of the loss of doctors, nurses, dentists, medics, ambulance workers, veterinarians, and medical students throughout Syria. Before the “die-in,” Dr. Holly Atkinson, director of the Human Rights Program at Mount Sinai, asked the crowd to “imagine a world without doctors, nurses, paramedics, and ambulance drivers, because if the Syrian and Russian forces prevail, that could become the reality for millions of people trying to survive in opposition held and besieged areas of Syria.” The demonstration illustrated that horrific world.

Speakers at the event emphasized that each loss of a medical professional is not only an individual tragedy but also one that affects an entire community’s access to healthcare. Dr. Tarakji, the president of SAMS, explained that “healthcare has been denied to Syrians through lack of access, prevention of aid delivery, and widespread attacks on medical facilities and health workers. The consequences of this strategy are devastating to the lives and health of civilians who remain in Syria, including the health workers struggling to save them.” According to USAID, there are currently 12.2 million people within Syria who need immediate humanitarian assistance. The loss of any healthcare workers greatly reduces Syrian civilian’s ability to receive medical care.

Attendees, many of whom were members of the local New York medical community, felt compelled to act on behalf of their counterparts who are working in dangerous conditions. Sarah Thappa, a first-year medical student from Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine represented a medical student like herself who was shot in Hama in 2012. Sarah said that she attended because, “We have the privilege of going to medical school, where we don’t have to think about war or any type of injustice or violence, so any call of support or any call to action to the U.N., however unheard, [matters]. Maybe it goes against deaf ears, but I think a first step is important. And to me, this is a first step that I can be a part of.”

Supporters hope the event will not only bring attention to the plight of medical workers in Syria, but also move the UN to enforce Resolution 2139. The resolution, passed in February 2014, calls for an end to indiscriminate attacks on civilians and respect for medical neutrality. The effort to call UN attention to the continued violations of medical neutrality did not end when the crowds dispersed. Physicians for Human Rights has created an online action to allow people who could not attend the rally to sign a letter to the UN Security Council to show their support and demand the enforcement of Resolution 2139.

The ‘die-in’ highlighted not only the tragedy facing Syrian healthcare workers, but the overwhelming support for them abroad. This event aimed to show doctors in Syria that they are not alone and have strong advocates around the globe. As Dr. Majed, public relations director of United Medical Office of East Gouta, said, “We cannot bring the doctors or the civilians who died back to life. But we can advocate to help the doctors who are in prison because they tried to help people and provide health services, and to protect the hundreds of doctors risking their lives to save others.”

This blog post was written by Laura Merriman, SAMS Advocacy Intern