August 23, 2016

Day 1 SAMS Global Response: Arrival

Day 1 SAMS Global Response: ArrivalArrived in Thessaloniki. SAMS Global Response is staying in a hotel just outside the city, near the government camps.

I arrived too late to join any of the clinics, so instead helped out with the day to day admin. The medical and field coordinators are trying to keep accurate records of all the patients who are treated. Finding a system which isn’t time consuming and can be quickly taught to new volunteers isn’t easy.

Most of the afternoon was spent trying to get excel and Google spreadsheets to communicate, and working out the best way to teach people how to use them. Not very exciting, but necessary.

Clinics finished at 7 and most volunteers were back after then. It’s a very international group; medical staff from Britain, Australia, Norway, a few British and Greek nurses, and Syrian and Palestinian translators. Working on the human resources spreadsheet I could see the amazing number of volunteers coming in the months ahead. There are 5 to 10 new volunteers arriving every week, from all over Europe. So all the clinics will be well staffed, and SAMS may be able to cover more camps in the coming months.

Alongside the volunteers SAMS is trying to employ Syrian doctors who are refugees in Greece to work in the clinics; to give them a livelihood, utilise their expertise and knowledge and reduce the dependence on volunteers.

There is lots of work being done to try and empower the refugees in the camps. I’ll write more detail about that in the coming days.

Day 2 SAMS Global Response

Every morning there is a briefing for all the volunteers. Any issues at the camps are discussed, updates are given about relations with the health service and local government and plans made for the days ahead.

Last week there were threats made to medical staff in two of the camps, and a man even drew a knife (albeit a very blunt one) on them in one incident. The field coordinator has now drawn up some security protocols for us to follow in the event of threats of violence, and made signs saying knives aren’t allowed near the clinic.

I’ve been assigned to Iliadis camp. It’s in a warehouse on the outskirts of Thessaloniki. It’s much like the other camps, rows of tents in and outside the building for people to live in. There are signs of more infrastructure; lots of covers providing shade, and rows of sinks with running water. Toilets are still just portaloos, and I didn’t see showering or bathing facilities.

The clinic is in a couple of plasterboard rooms in the corner of the warehouse. There are two examinations couches, and a fridge for storing medication. Its basic but functional. We set up our triage table and began registering patients. All patients are given a blue notebook when they first attend, which their name, DOB, languages spoken and tent number are recorded in. Its used to keep track of their visits to the clinic so we have a crude history of their presenting complaints, and can keep a record of whats been done for them. We ask all patient to bring their notebook when they attend, and we won’t see them unless they have it. Some are annoyed by this, but most accept the system without complaint.

The morning session was mostly parents with young children worried about fevers or coughs. We had to halt the clinic for 30 minutes when an older patient grew angry and verbally abusive and smashed his fist into our triage table because he thought other people were being seen before him.

We closed up the clinic and went outside to show we wouldn’t tolerate that kind of violent behaviour. The other patients – mostly the parents with children – were all trying to reason with the aggressor and persuade him to stop, but he wouldn’t listen.

After 30 minutes things quieted down and we set up again. The camp president came over and apologised for the mans behaviour and said if we ever experienced that again to come and seek him out and he would sort it immediately.

Patients we saw were mostly young children with fevers and coughs, or adults with wounds. A big problem in the camps are mosquito bites, lack of hygiene facilities exacerbates this as small bite wounds become infected through lack of hygiene and poor wound care, and become much more uncomfortable.

Many patients feet and legs were covered in bites, and several needed pus draining from infected wound sites. All patients are given a blue notebook which has their name, DOB, languages spoken and tent number in it. Its used to record their visits to the clinic so we have a crude history of their presenting complaints, and can keep a record of whats been done for them.

There were a couple of patients who needed referrals chasing up, and a couple suffering complicated genetic disorders that needed more intensive management, but the majority of cases were simple and easily treated.

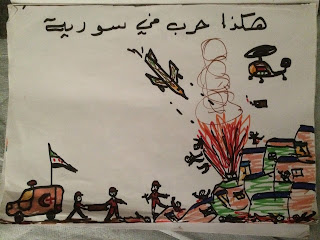

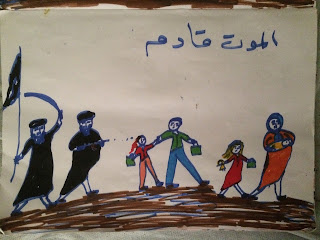

In a quiet moment I was taking pictures of the graffiti on the warehouse walls and man waved me over to come with him. I accompanied him to his tent and he showed me a book of pictures he had drawn illustrating the trials Syrians faced in Syria and on their journeys seeking refuge. The pictures showed the whole gamut of terrible experiences suffered by Syrians; from being bombed and tortured by the Assad regime, oppressed by ISIS, beaten at the Turkish border, having their children or organs sold by human traffickers, being abused by the Greek police, and their abandonment by the UN and EU. The man and his family were originally from Aleppo, before having to flee, and he had drawn the pictures based on his own experiences, and what he had heard from others in the camp.

The drawings were just a small sample of the horror that many of the camps inhabitants had experienced. Behind many of the smiling and friendly faces were deep wells of trauma.

Volunteers were coming to the camp regularly to organise activities for the children and try and keep them occupied. The volunteers played jump rope and other games with the children, allowing their parents to get on with other things. While obviously welcome, it was a worrying sign that people were becoming institutionalised. Everything the volunteers were doing could have been organised by the refugees themselves, if given the resources and time. But this isn’t forthcoming, so they end up reliant on volunteers for simple tasks.

For example, volunteers are going to some camps and digging gardens for the refugees to grow food in. The refugees aren’t allowed to do this themselves as the military administration that runs the camps is paranoid about allowing anything that might be used as a weapon in to the camp, so no picks or shovels can be given to them. This conscious disempowerment deprives them of the ability to self-organise and do these things themselves, making their time in the camp even more boring, frustrating and purposeless.

SAMS is working to train up refugees as community healthcare officers who can take charge of the health needs of the community, through being given control of a healthcare kit, responsibility for calling ambulances and advocating for the health needs of the camp residents. At present even simple things like plasters can only be obtained from the SAMS clinic, and refugees cant communicate their health needs properly to the camp administrators, meaning ambulances are called out inappropriately. An ambulance was called last week in the middle of the night for a case of toothache, something that could have easily been managed in the camp until a more reasonable hour, if the refugees had ready access to analgesia, and someone with the knowledge and training to dispense it safely.

Its hoped that by drawing members of the camp community into providing healthcare, SAMS can empower the community, strengthen their relationship with the people they are serving, and strengthen the communities position versus the camp management and Greek government. At present the camps are little more than warehouses for humanity, and will remain so unless the people in them, and those supporting them, organise to change that.